1. Introduction

In today’s interconnected world, we constantly encounter discussions revolving around conflicts, the ballooning US debt, de-dollarisation, democracy vs autocracy, the emergence of a multi-polar world, and the increasing societal and international divisions. These themes paint a picture of chaos, decline, and a seismic shift in power dynamics.

Amidst these contesting opinions and data points, we as investors face a daunting task:

“How do we create + capture alpha amidst the turbulence of our times?”

The solution lies in recognising the intricate interplay of macroeconomic and geopolitical factors and the frontier technology ecosystems. The COVID-19 pandemic has only reinforced our reality characterised by multipolarity, where geopolitics isn’t a static backdrop but a dynamic force shaping the contours of frontier technology ecosystems.

This forms the basis for our macroeconomic thesis that contextualises all these developments as we pursue our journey to capture significant alpha while building the essential East to West Corridor.

2. Understanding the global economic, security, and technological axes

As they say, ‘chaotic and risky times are the best opportunity to generate alpha.’ To understand the shifting global trends and to identify growing markets and asset classes, we would like to analyse the interplay of three critical domains:

2.1 Economic Power Center

Besides labour, capital, and technological progress, economic growth also depends on the political stability that enhances consumer and investor sentiment and societal trends (demographic dividend, polarisation, crime, drugs, cultural & religious divides, and economic inequalities). Global geopolitics and supply chain movements are also increasingly playing a pivotal role.

The following trends can be highlighted for global economic power:

2.1.1 Shift of power from ‘West’ to ‘East’ / ‘Global North’ to ‘Global South’ –

Various theories, rooted in evident economic realities, highlight the narrative of a global economic power shift. Fareed Zakaria’s ‘Rise of the Rest’ theory suggests the ‘relative decline’ of Western economies, primarily the US and EU, is not a decline but a broadening of the global economic landscape and the emergence of ‘regional centers’ of prosperity. Others say that the US global influence is over and point to de-dollarisation, a multi-polar world, and internal instability in the US. Whether you believe in a benign or a drastic version, western economies’ share of macroeconomic indicators – global GDP, industrial production, and world trade are shifting to Asia, the Middle East, and Africa, changing the global opportunities and risk landscape.

A. GDP and Income Shifts: Eastern entrants into the Wild Wild West economic club

As early as 2011, a McKinsey Global Institute Analysis projected a move of the economic centre of gravity towards Eastern economies. Another analysis in 2007 by a professor at the London School of Economics and Political Science and LSE Global Governance projected that by 2050, it will literally be between India and China.

This analysis is borne today by global macroeconomic indicators.

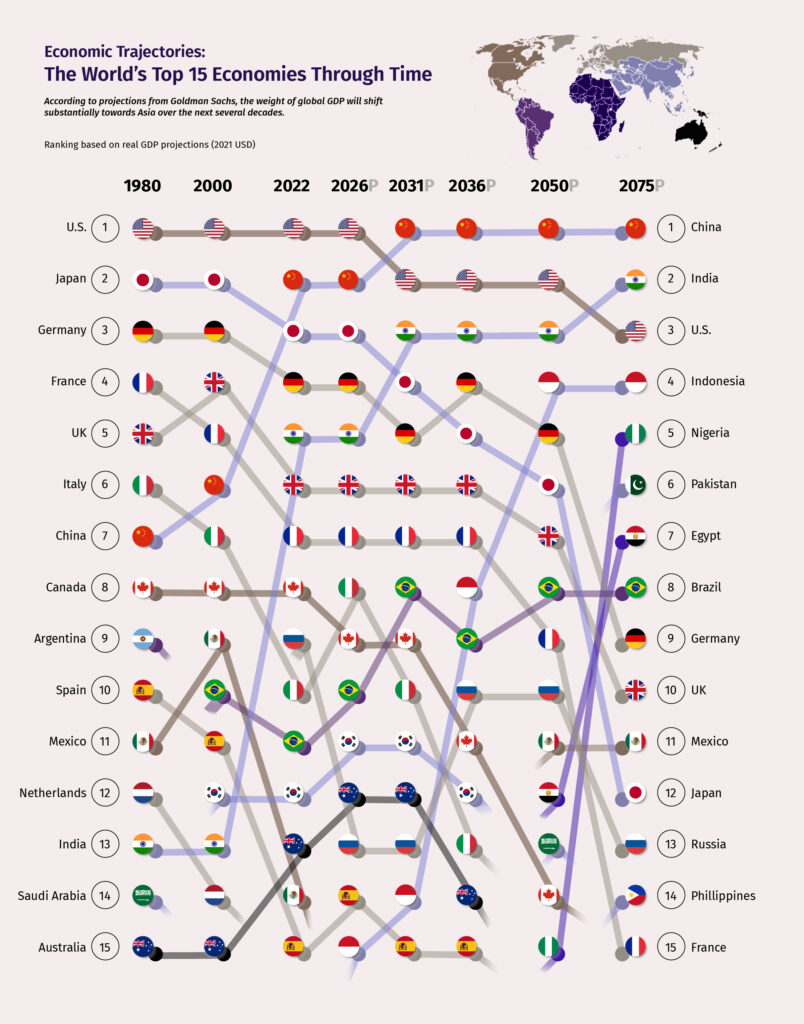

- As per projections (Figure 2), Asian economies – China, India, Indonesia, and Brazil will dominate the top 10 slots in the coming decades, and China is set to surpass the US by 2035 and India to surpass by 2075.

- India recently overtook the UK to become the world’s fifth-largest economy in nominal GDP terms and is poised to breach into the top 3 by 2027-28. By PPP (Purchasing Power Parity), India is already among the top three.

- Recent economic analysis suggests that BRICS nations (minus the new entrants) have surpassed the G7 economies (discussed in the section on ‘Emerging Multi-polar economic order’)

- In addition, growing GCC economic powerhouses, UAE and Saudi Arabia, are investing in non-oil diversification initiatives using their oil wealth, Sovereign wealth funds, and growing business prowess to change the regional landscape.

The global GDP shift has also been accompanied by a decline in wealth inequalities between countries. The gap between the average incomes of the richest 10% of countries and the average income of the poorest 50% of countries dropped from around 50X to less than 40X.

B. Trade and manufacturing re-alignment from West to East

A recent Standard Chartered Bank report titled ‘Future of Trade 2030’ highlights four main global trade and investment trends:

- Shift in trade momentum from mature Western markets to emerging economies’ high-growth corridors in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. These regions will drive export volumes from USD 9 trillion in 2021 to USD 14.4 trillion in 2030, outpacing the global trade growth rate by 4% points.

- Thirteen emerging markets, including India, UAE, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, Vietnam, and Nigeria, will drive most of this growth, accounting for 73% of all exports and 69% of all imports.

- Rapid industrialisation and manufacturing opportunities in Asian economies creating export markets + growing demand, strong purchasing power, and state spending expanding import markets in the MENA region + regional trade agreements creating intra-region trade opportunities (Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreements in the Middle East, African Trade Initiative, Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership in Asia).

- Trends of risk diversification (to insulate from geopolitics, trade wars, pandemics, and other obstructions) and rebalancing will also help ‘neutral’ Asian and MENA economies as the West diversifies from China.

These are the main trade corridors:

- Intra-ASEAN: 8.7% annual growth rate, reaching USD 0.8 trillion

- South Asia – ASEAN: 8.6% annual growth rate, reaching USD 0.3 trillion

- South Asia – Africa: 8.2% annual growth rate, reaching USD 0.2 trillion

- South Asia – Middle East: 7.0% annual growth rate, reaching USD 0.5 trillion

- East Asia – ASEAN: 6.3% annual growth rate, reaching USD 2.1 trillion

- Intra-East Asia: 3.4% annual growth rate, reaching USD 2.2 trillion

C. Bolstered by favourable demographic factors

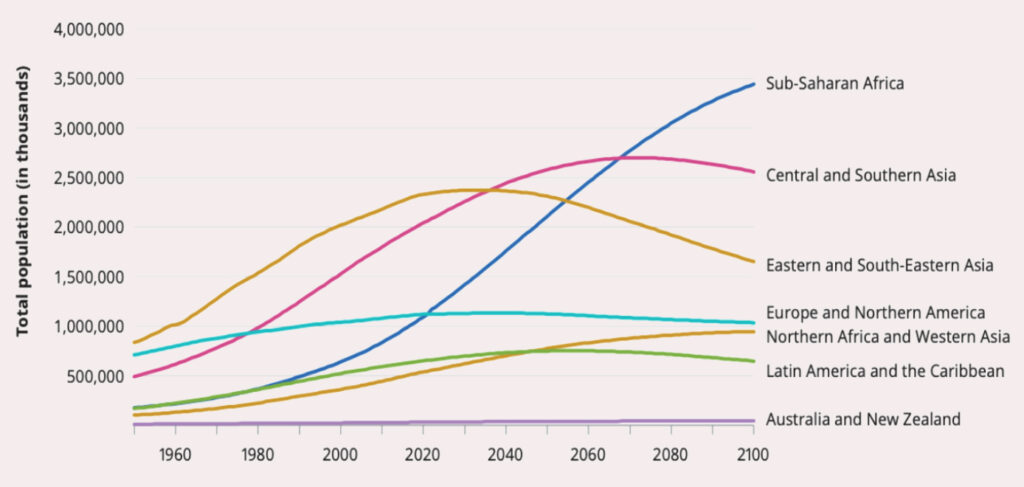

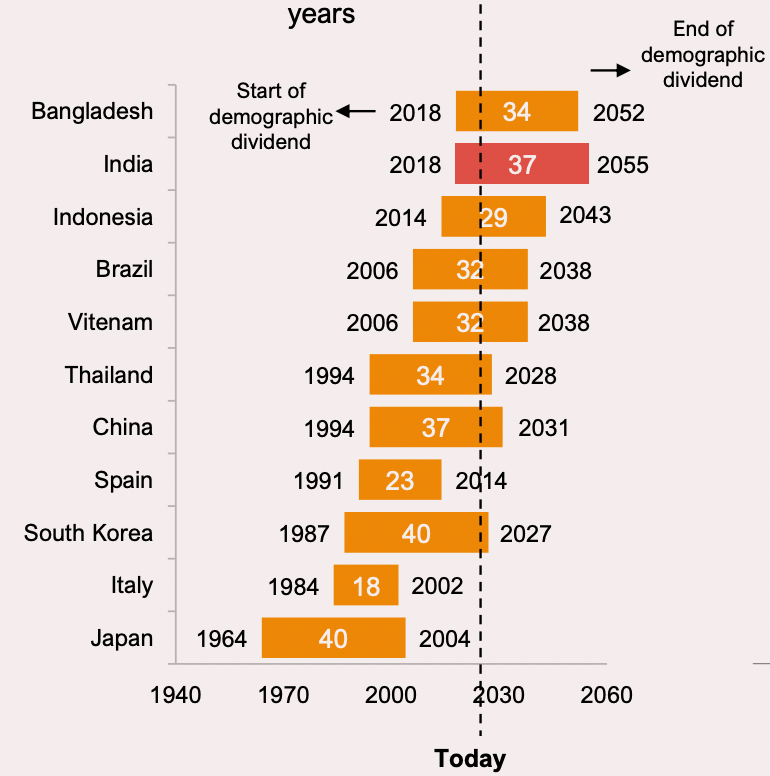

This shift is not transient but supported by the structural transformation of global demographics, political systems, and societal trends. Over the past fifty years, the global population has grown at an unprecedented rate due to various factors, including the absence of major conflicts like World Wars, advancements in medical science, the agricultural revolution, reduced child mortality, and favourable social and cultural norms, especially in emerging nations. This trend is projected to persist in regions like Africa and parts of Asia – South, Western, and Central – for the next five to six decades.

Simultaneously, emerging economies, such as India, are reaping the benefits of demographic dividends influencing global economic trends and growth. This is expected to continue for at least the next two to three decades. This sustained growth is largely attributed to solid policies, socio-economic stability, and strong political frameworks within these countries.

2.1.2 Emerging multi-polar economic order: Minilateralism, Regionalisation and challenges to Dollar Hegemony

The above-stated shifts in macroeconomic indices have strengthened a multi-polar economic order. This has allowed mid-powers – India, UAE, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, Turkey, etc. to mediate financial domination by the superpowers (US & allies and China and Russia) and attract economic opportunities in the tit-for-tat environment. In the process, they are creating alternative power centres and models of governance, which we define as –

A. A move from multilateralism to miniliteralism

B. Globalisation to regionalisation

C. Emergence of BRICS/shifts away from dollar hegemony

A. Minilateralism: A case for interest-based alliances

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine marked a watershed in the move away from multilateralism. For years, criticism has been levelled at the ‘Western’ bias of the global economic (Bretton Woods, IMF, World Bank, dollar hegemony), security (NATO, US military alliances), and political (United Nations) architecture. There have been talks of reforming the Security Council, inclusion in the Bretton Woods institutions, and giving a seat at the table to the two big-size players, India and China.

However, western sanctions on Russia’s energy, a ‘bullying’ of every power to toe the line, and the freezing of Russian assets spurred the mid-powers into a unified front. Since then, key global issues have increasingly been navigated in smaller interest-driven forums rather than global (western) ideology-driven forums. This trend of mini-literalism has allowed mid-powers more room for manoeuvring, concessions, and power projection. From I2U2 (India, Israel, UAE, and the US) to the Quad to regional technology sharing forums to solar and climate alliances – the ‘Global South’ has used these forums to set the agenda, participate in decision-making in critical issues such as agriculture (food security), climate change, energy security, technology governance and more active diplomatic role in the US-China superpower rivalries.

B. Balancing globalisation and regionalisation

While growth in global trade is predicted to grow by 70% to about USD 30 trillion by 2030, and inter-continent investment will remain relevant –regionalisation of trade, investment, and movement of resources and information cannot be ignored. With a post-pandemic move from ‘just in time’ supply chains to ‘just in case’ supply chains signifying ‘nearshoring’, and the emergence of regional centres of prosperity in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East – this trend needs to be closely watched.

A recent BCG report illustrated this trend with reference to Africa, where trade is expected to grow faster than the global average at 3.3% per year by 2032. As per the figure below, regional collaboration boosted by the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) and shifts to China, GCC, and India (and other emerging economies) will be major trends.

C. The BRICS challenge to G7

Perhaps one of the biggest examples of minilateralism and challenge to the Western-led world order and dollar hegemony is the newly expanded BRICS (now includes UAE, KSA, Iran, Egypt, and Ethiopia). BRICS + countries represent USD 2.5 trillion economic powerhouses, 42% of the world’s oil production, 72% of critical minerals, and major infra funders.

In its stated aims, BRICS is envisaged as a small coalition of like-minded states to advance multipolarity and position the ‘Global South’ at the forefront of the global agenda. In its attempted actions – increased trade within bloc members, financing for infra projects through the BRICS New Development Bank, and promoting local currency usage – it is a challenge to the US-led WTO, World Bank/IMF, and the dollar. While BRICS is not expected to supplant the West, initiatives like Rupee/Dirham-denominated bonds, BRICS Bank’s lending to critical technology, and local currency transactions – can create vital opportunities in member countries.

The challenge to the dollar hegemony

One of the most disruptive impact of BRICS can be on the dollar hegemony as world’s largest producers, consumers, oil sellers & buyers, and big markets begin focusing on local currency transactions for vital trade. Historically, various countries and regions have tried to lessen their dependence on the U.S. dollar, but these attempts have not been widespread or comprehensive. Even today, there is no substantial evidence demonstrating that the dollar’s supreme status is under threat, but there are definite signs this time that it is different.

- Global US dollar forex reserves had dropped to a historical low of 58% in 2023.

- There are a growing number of countries across Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America exploring alternatives to the dollar for purposes such as trade invoicing, forex reserves, financial settlements, and debt issuances.

- BRICS nations are exploring a BRICS currency to rival the dollar’s dominance. Discussions on yuan-based oil trades between Saudi Arabia and China, yuan clearing arrangements between Brazil and China, and significant yuan-based trade between China and Russia signal a shift in global finance. Additionally, the Reserve Bank of India is boosting the rupee’s global presence by enabling rupee trading in 22 countries, while an India-UAE agreement on Local Currency Settlement further diversifies trade away from the dollar.

All these indicate a shift away from a single dominant global power towards a more multipolar world order in the face of deepening fragmentation, evolving narratives, and aspirations toward a new and more democratic international economic order.

2.2 Security and Military Sphere

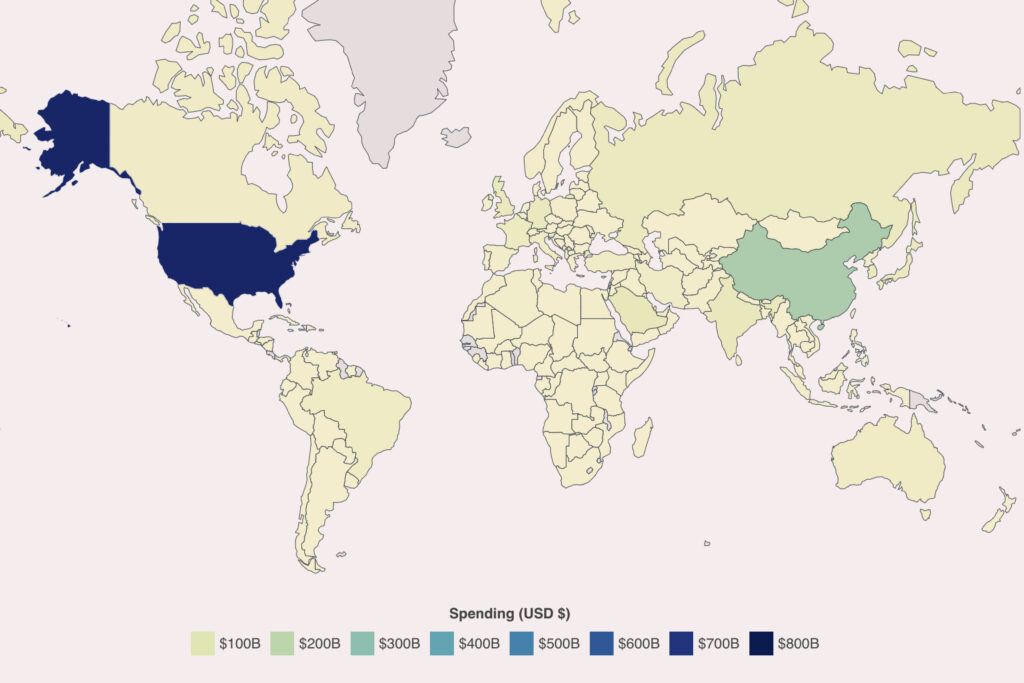

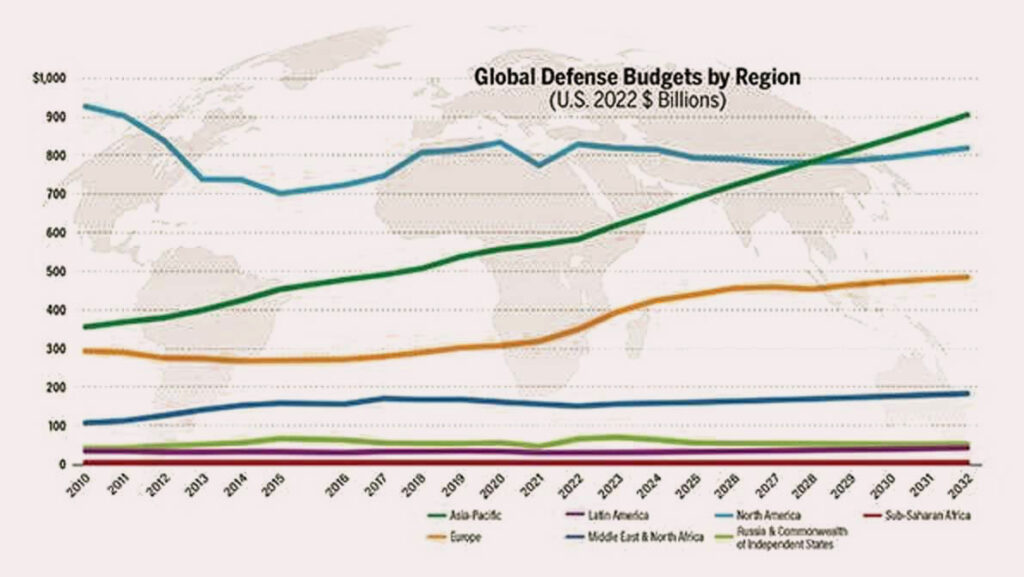

In this global domain, the US (and some allies) heavily outweighs all other countries in military spending, defence exports, and the security levers it has built worldwide. China is getting stronger and is on a spree to fortify its defences, but it can only effectively project power in Asia. However, it is now getting entangled in security dynamics in ME and Africa. Neither are Chinese defence forces battle-tested nor do have the experience of being an influential power broker.

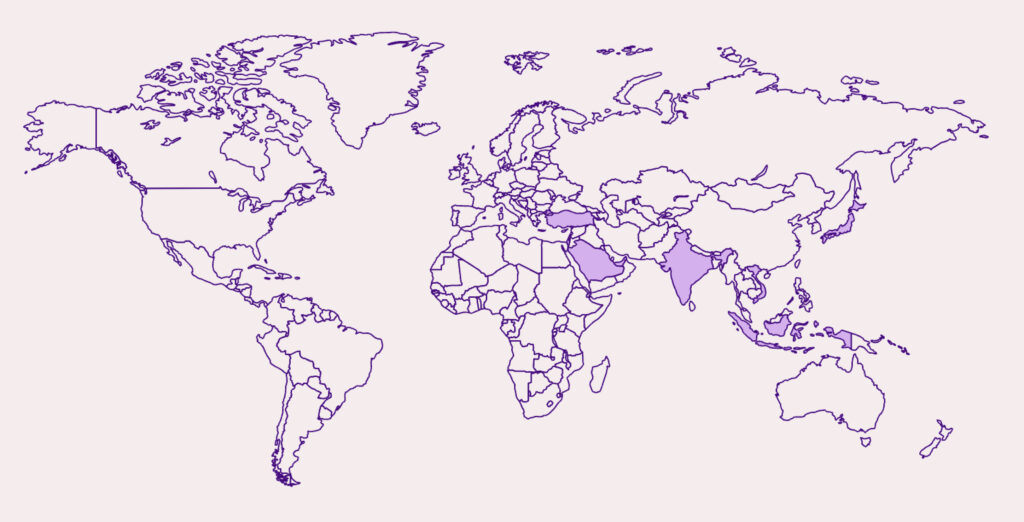

However, with economic power, surplus budgets, and increased international standing comes the desire to expand military and security capabilities. This is the driving force behind several mid-powers’ localisation (and export) initiatives, along with increased military spending on imports. This is also leading to critical tech/defence/space/energy cooperation between leading economies such as India, UAE, and Saudi Arabia and East Asian nations such as Japan, Korea, and Taiwan.

Some examples are noteworthy – India striving to increase its military diplomacy in the GCC- by promoting defence exports and military security cooperation through joint military exercises, counterterrorism and security cooperation, intelligence sharing, AI, electronic warfare and cybersecurity, etc.

- Indian Navy’s INS Visakhapatnam and INS Trikand participated in the bilateral exercise ‘Zayed Talwar’ with the UAE in 2023. This exercise aimed at reinforcing interoperability and collaborative efficiency.

- Goodwill visits by Indian ships to Saudi ports have been one of the major components of recent defence cooperation with the Kingdom.

- Establishing linkages b/w defence industries- both state-owned and private firms.

Transfer of Technology (ToT) has been a key theme

Examples:

– India’s Hindustan (HAL) and the UAE’s defence firm, EDGE, signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to explore the possibility of joint design and development of missile systems and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) in Feb 2023 during International Defence Exhibition and Conference (IDEX).

– Saudi Arabia’s Power For Defence Technologies Co (PDTC) inked an agreement with India’s DPSU Bharat Electronics Limited (BEL) to work jointly on technologies linked to aerospace, including both civilian and defence applications.

Superpower rivalries leading to restrictions on critical defence/military technology – semiconductors, chips, AI and supercomputing, surveillance software, and rare earth minerals are also a feature of the global order that will escalate as China-US relations deteriorate. It will be necessary to identify ‘neutral’ and ‘strategic’ countries that can minimise sanctions/restriction damages and, in fact, be a beneficiary of supply chain reconfiguration.

Among other countries, India, and Saudi Arabia & UAE in the Middle East again fall under this category, and the moves these nations have made internally as well as with other countries indicate that they are both well poised to capture the realignments due to changing geopolitical dimensions.

Internally within India, to reduce dependency on its traditional major defence importers such as Russia, France, USA, the country has provided a major thrust towards self-reliance and localisation via initiatives such as Aatmanirbhar Bharat and Make in India, with an ultimate aim to become a net exporter in the defence sector. These initiatives are enabled by- 1. Positive Indigenisation Lists; 2. promotion of local manufacturing and setting up of defence Industrial Corridors in states like Uttar Pradesh and Tamil Nadu to bolster domestic production; 3. initiatives like ADITI, iDEX, and iDEX Prime, TDF by DRDO to foster innovation and incentivise privatisation; 4. liberalised FDI policies, streamlined export processes; 5. Increased defence budget allocations and R&D earmarking further strengthen India’s localisation efforts.

In addition, India is also strengthening its relationship with the West through partnerships like Quad and exploration of new technology, innovation, and defence agreements and initiatives such as INDUS-X.

Saudi Arabia and UAE, with their disproportionate amount of capital and willingness to deploy it domestically as well as around the world in pursuit of strategic objectives, are also positioned positively in this. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia was the second largest defence sector importer in the world behind India during 2018-22, and its major importers being the US and the UK. This can be attributed to the relative nascency of the local industry, whose origins date back to the 1970s. However, in recent years, the Kingdom has been making significant strides toward becoming self-reliant in the defence sector via Saudi Vision 2030. To enable its objective to localise more than 50% of spending on military equipment and services by 2030, GAMI and SAMI were established. The General Authority of Military Industries (GAMI) oversees and regulates the defence sector, managing military procurement and contracts while SAMI, established in 2017, is a national champion driving localisation goals by forming joint ventures between Saudi and international military production companies.

Further, the UAE too has made similar moves to reduce its dependency on imports. In addition to launching a free zone for the military and security sector, the country’s military awarded $6.4B worth of contracts to local firms.

2.3 Technological and Digital Landscape

Over the past two to three decades, the United States and China have emerged as leading hubs for startups and technology development. In the US, Silicon Valley has spearheaded innovation backed by venture capital, private investment, academic institutions, and government grants. China has seen significant advancements in critical technologies like AI, propelled by state-led initiatives and long-term strategic planning.

While the top 10-20 companies by market capitalisation are the US, China, and some European companies, over the last decade and a half, there is strong evidence of the trend of decentralising global tech and knowledge work, with the exponential rise of the startup/entrepreneurial ecosystems in India and other emerging economies. One crucial indice here is the drop in the share of global VC-backed innovation in the Bay Area from 40 to 20%. Some of this has gone to other US cities, but funding is also being channelised to the cities of India, the Middle East and other Asian and African startup ecosystems.

India stands out due to its large, educated, aspirational, and tech-savvy consumer base, fueled by significant inflows of private capital and government support. Measures such as encouraging foreign direct investment (FDI), fostering an environment for innovators to thrive, and also the efforts to create the vital Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) have contributed significantly to India becoming a breeding ground for frontier technology entrepreneurs. The country has 68k+ startups launched (as of 2023), $141B+ capital inflows (as of 2023) and the third-largest number of unicorns globally, with many more soonicorns in line. Top sectors that have reached maturity include EnterpriseTech, Ecommerce, Fintech, and ConsumerTech, among others. In the recent past, frontier technology startups working in AI, Blockchain, Space, Defence, and other emerging technologies & sectors have attracted a significant flow of entrepreneurs, people, and investors supported by the favourable evolving regulatory involvement.

In the Middle East, Israel has earned the moniker of ‘Startup Nation’ for its leadership in frontier technology startups. Countries like the UAE and Saudi Arabia have created a conducive environment for entrepreneurs and investors with their sandboxing and regulatory-led tech development. This has been supported by the notable allocations of capital towards frontier technologies by their Sovereign Wealth Funds and other institutional investors. These regions are also unlikely to be caught in the US-China tech cross-fire.

The COVID-19 pandemic has further accelerated the growth of startup ecosystems worldwide, particularly in India, the Middle East, Africa, and Southeast Asia. This is owing to the rapid adoption of anything digital during the lockdowns and the eventual permanent shifts in the way consumers use their digital products. This is further supported by increased adoption of remote and flexible working, rising rents and taxes in megacities, newly emerging national markets, and tech-focused government policies creating global ‘Silicon Valleys’.

However, it is to be noted that many of these ecosystems, including in India and other regions in the East, are yet to reach a significant maturity level 1. In terms of the consumers who would eventually be using these new age offerings built on frontier technologies such as AI, Metaverse, etc. 2. From an investor’s viewpoint, the ecosystems haven’t matured to the level of the US market, for example. In the US, there are frequent M&As, IPOs, etc., offering ample exit opportunities and significant value creation potential for investors in the region. We, as active investors and ecosystem enablers, realise that this is part of the evolution of any entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Overall, the ‘frontier’ startup ecosystems in the emerging nations in the East have become ripe grounds for the next generation of frontier technology companies to emerge and transform their respective economies.

3. Honing in on the Alpha: Critical Markets and Sectors

A convergence of the above-stated economic, security, and tech trends in certain markets and segments can create opportunities for alpha returns. Let’s do the math:

Economic growth (underpinned by political stability, demographic advantage, capital to deploy, talented workforce, stable societal indicators)

+

Military power projection (increased spending, local innovation, ‘neutrality’ in superpower/geopolitical power clashes)

+

favourable tech indicators and ambitions

= ALPHA

Key geographies to watch out for:

India, UAE, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Japan, Vietnam, Indonesia

Key technologies and sectors include:

- Engineering– Defence, Aerospace, Energy, Climate

- Data – AI, Blockchain, Metaverse, AR/VR

In our upcoming technology deep dives, we’ll delve into specific sectors, examining the nuanced opportunities that lie within each.

For our reader:

This macro thesis serves as the framework and provides a broad overview of the lens through which we observe developments happening in our chaotic world and, more specifically, in our regions of interest. This will be a living and breathing thesis, taking into account dynamic shifts and evolving as we pursue our journey to capture significant alpha while building an active East to West Corridor.

Authors : Rahul Nagaraj, Shraddha Bhandari (Confluence Consultants)

Contributors : Pranav Sharma, Indrajeet Sirsikar